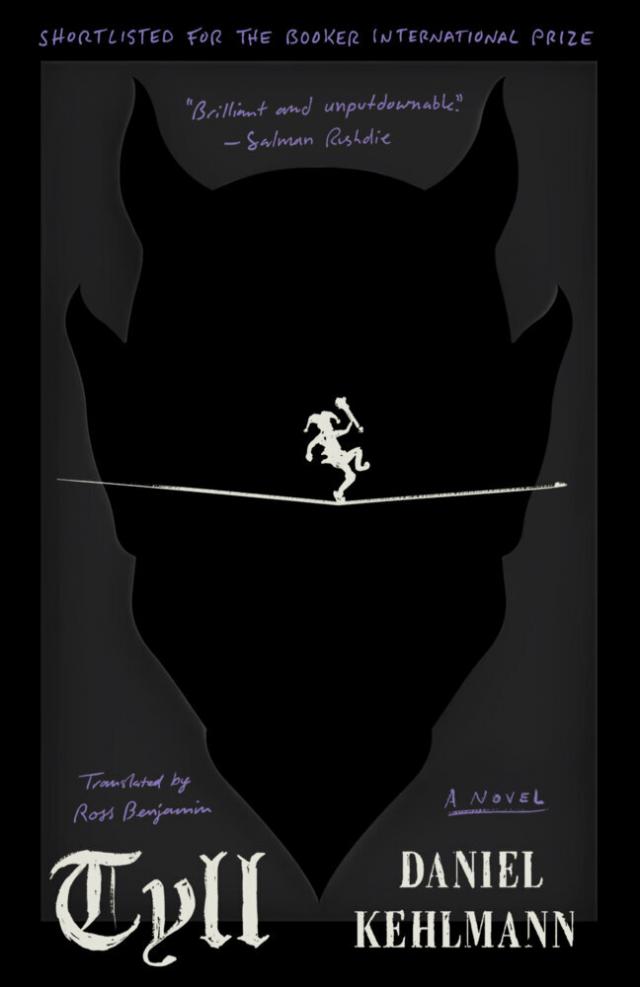

Tyll

Taschenbuch

Penguin Random House; Vintage (2021)

352 Seiten; 18 mm x 131 mm

ISBN 978-0-525-56272-6

Vorübergehend nicht lieferbar, voraussichtlich ab 2024 lieferbar

€ 21,50

Besprechung

**Shortlisted for the Booker International Prize**

Brilliant and unputdownable. Salman Rushdie

Profoundly enchanting. . . . A magnificent story. . . . A spellbinding memorial to the nameless souls lost in Europe s vicious past, whose whispers are best heard in fables. The New York Times Book Review

Kehlmann is a gifted and sensitive storyteller. . . . He is a playful realist, a rationalist drawn to magical games and tricky performances, a modern who likes to look backward. . . . Brilliant. The New Yorker

Prodigiously imaginative. . . . Brilliant, blackly sardonic. . . . In Mr. Kehlmann s unforgettable joker we have a picture of humankind in all of its madness and strutting pride. The Wall Street Journal

Kehlmann, like Tyll, is a trickster. . . . Entertaining us like a jester on a tightrope and reminding us of the danger of a fall. Washington Post

A laugh-out-loud-then-weep-into-your-beer comic novel about a war. . . . Ambitious, clever, tricksy, self-reflective. . . . It s operatic in its gestures and heartbreaking in its absurdity. The Times (UK)

A rip-roaring yarn. . . . It plunges a modern reader into an astonishingly violent and dirty alternative reality. . . . But Tyll is a very funny novel, too. . . . There are many ways in which this strife-torn Europe, fractured by religion, intolerance and war, is a reflection of our own times. The Guardian

Textauszug

Kings in Winter

I

It was November. The wine supply was exhausted, and because the well in the garden was filthy, they drank nothing but milk. Since they could no longer afford candles, the whole court went to bed in the evening with the sun. The state of affairs was not good, yet there were still princes who would die for Liz. Recently, one of them had been here in The Hague, Christian von Braunschweig, and had promised her to have pour dieu et pour elle embroidered on his standard, and afterward, he had sworn fervently, he would win or die for her. He was an excited hero, so moved by himself that tears came to his eyes. Friedrich had patted him reassuringly on the shoulder, and she had given him her handkerchief, but then he had burst into tears once again, so overwhelmed was he by the thought of possessing a handkerchief of hers. She had given him a royal blessing, and, deeply stirred, he had gone on his way.

Naturally, he would not accomplish it, neither for God nor for her. This prince had few soldiers and no money, nor was he particularly clever. It would take men of a different caliber to defeat Wallenstein, someone like the Swedish king, say, who had recently come down on the Empire like a storm and had so far won all the battles he had fought. He was the one she should have married long ago, according to Papa s plans, but he hadn t wanted her.

It was almost twenty years ago that she had instead married her poor Friedrich. Twenty German years, a whirl of events and faces and noise and bad weather and even worse food and completely wretched theater.

She had missed good theater more than anything else, from the beginning, even more than palatable food. In German lands real theater was unknown; there, pitiful players roamed through the rain and screamed and hopped and farted and brawled. This was probably due to the cumbersome language. It was no language for theater, it was a brew of groans and harsh grunts, it was a language that sounded like someone struggling not to choke, like a cow having a coughing fit, like a man with beer coming out his nose. What was a poet supposed to do with this language? She had given German literature a try, first that Opitz and then someone else, whose name she had forgotten; she could not commit to memory these people who were always named Krautbacher or Engelkrämer or Kargholz-steingrömpl, and when you had grown up with Chaucer, and John Donne had dedicated verses to you fair phoenix bride, he had called her, and from thine eye all lesser birds will take their jollity then even with the utmost politeness you could not bring yourself to find any merit in all this German bleating.

She often thought back to the court theater in Whitehall. She thought of the small gestures of the actors, of the long sentences, their ever-varying, nearly musical rhythm, now swift and clattering along, now dying gradually away, now questioning, now bristling with authority. There had been theater performances whenever she came to the court to visit her parents. People stood on the stage and dissembled, but she had grasped at once that this was not so at all and that the dissembling too was merely a mask, for it was not the theater that was false, no, everything else was pretense, disguise, and frippery, everything that was not theater was false. On the stage people were themselves, completely true, fully transparent.

In real life no one spoke in soliloquies. Everyone kept his thoughts to himself, faces could not be read, everyone dragged the dead weight of his secrets. No one stood alone in his room and spoke aloud about his desires and fears, but when Burbage did so on the stage, in his rasping voice, his very thin fingers at eye level, it seemed unnatural that men should forever conceal what transpired w

Langtext

The New York Times Best Historical Fiction of 2020

The Guardian's Best Fiction of 2020

Thrillist's Best Books of the Year

Daniel Kehlmann transports the medieval legend of the trickster Tyll Ulenspiegel to the seventeenth century in an enchanting work of magical realism, macabre humor, and rollicking adventure.

Tyll is a scrawny boy growing up in a quiet village until his father, a miller with a forbidden interest in alchemy and magic, is found out by the church. After Tyll flees with the baker s daughter, he falls in with a traveling performer who teaches him his trade. As a juggler and a jester, Tyll forges his own path through a world devastated by the Thirty Years War, evading witch-hunters, escaping a collapsed mine outside a besieged city, and entertaining the exiled King and Queen of Bohemia along the way.

The result is both a riveting story and a moving tribute to the power of art in the face of the senseless brutality of history.

Translated from the German by Ross Benjamin

Beschreibung für Leser

Nominiert: Man Booker International Prize, 2020

- birthday gifts for men

- gifts for grandfather

- father gifts

- dad gifts

- london

- class

- family

- drama

- time

- gifts for women

- music

- gifts for men who have everything

- gifts for boyfriend

- kindle books

- top books

- novels best sellers

- historical fiction best sellers

- best sellers

- books best sellers

- books

- novel

- fiction

- funny books

- history

- fiction books

- novels

- war books

- science

- animals

- friendship

- magic

- folklore

- adventure

- historical novels

- historical fiction

- German

- humor

- you should have left daniel kehlmann